NBA

Portland’s Title Hopes Hinging On Zach Collins’ Adaptability

Letting Al-Farouq Aminu walk in free agency was a long time coming for the Portland Trail Blazers.

He was an integral part of the team’s surprisingly stingy defense over the past few seasons, checking several positions over the course of 48 minutes and providing Portland with a sense of disruption and overall activity – both on and off the ball – its more physically-limited defenders couldn’t. The Blazers’ lack of size in the backcourt and ultra-conservative scheme made them imminently exploitable at certain points of the floor; Aminu’s energy and versatility often proved key to staunching the bleeding of those inevitabilities.

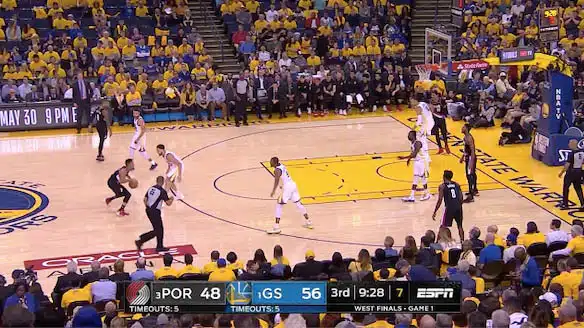

But he’s gone now, a loss that comes as no surprise after his playing time steadily diminished throughout Portland’s run to the Western Conference Finals. How the Blazers replaced Aminu is what’s raised eyebrows, and it could be the deciding factor between them building on last season’s progress and taking a step back in a wide-open Western Conference.

Zach Collins is a far different player than Aminu, as well as fellow offseason departure Moe Harkless. Their theoretical value to Portland rested on defense first and foremost, but also a comfort playing without the ball offensively. One problem: Aminu and Harkless, despite some fleeting stretches of hot shooting, weren’t even close to reliable from the beyond the arc. Worse, defenses felt comfortable leaving them away from the ball to make life extra hard on their star teammates, a dynamic that annually neutered the Blazers’ offense when it mattered most.

But Neil Olshey didn’t account for the absence of two stalwarts by bringing in a defensively-limited forward who could nevertheless help relieve pressure on Lillard and McCollum, further juicing an offense that finished an overlooked third in offensive rating last season. Kent Bazemore is Portland’s only significant addition on the wing, and he was acquired from the Atlanta Hawks before free agency. Mario Hezonja isn’t the answer for a team with aspirations of legitimate contention, especially playing small forward, and Gary Trent Jr. is a second-round pick who rarely saw the floor as a rookie.

It’s Collins who’s tasked with sopping up most of the Blazers’ newly-available minutes at power forward. From a team-building standpoint, increasing his responsibilities is certainly the right approach. Portland traded up in the 2017 draft to take Collins at No. 10; he wasn’t going to be an energy guy off the bench forever and likely would have proven over-qualified for that status given even marginal growth over the summer.

Whether the role Collins is primed to play this season is the right one, though, is a matter worthy of disagreement.

He’s best-suited for center long-term; even the Blazers are surely admitting as much in private. But Collins’ time in the middle will almost certainly be few and far between in 2019-20 given the odd makeup of Portland’s roster. Bazemore is the lone off-ball perimeter player who doubles as a plus defender and semi-threatening long-range shooter, and he’s way too small to check the likes of LeBron James and Kawhi Leonard. There will be many important moments for the Blazers when Rodney Hood is left to guard the best players in the world.

Collins will inevitably be put on that island sometimes, too. His ability to move his feet in space and manage strong contests at the rim from behind is the chief justification behind his potential ability to hold up at power forward full-time. Collins isn’t quite Clint Capela of a couple years ago. Portland won’t readily switch him onto superstar ball handlers like it did Aminu, either, but his combination of quickness, length and impeccable timing as a shot-blocker makes him switch-worthy under duress of time and score or specific opponent regardless.

The Blazers didn’t always switch across four positions with Aminu and Harkless on the court, but the option of doing so when necessary mitigated much of the inherent weakness presented by their personnel. Portland was happy to let offenses target Lillard and McCollum on the block in those circumstances, confident the opposition assumed posting up undersized perimeter defenders was a better means of attack than sizing up Aminu.

Teams won’t feel the same way when it’s Collins venturing outside the paint to corral playmakers. His nagging tendency to foul will come into play there, too. And when the Blazers opt against switching actions involving Collins and a guard, they’ll be subject to exactly the type of defensive rotations their long-running scheme has sought to minimize.

It would be remiss to overlook the potential impact of Portland’s collective length up front. No team in the league will start a frontcourt tandem longer than Collins and Hassan Whiteside, and the same will be true once Jusuf Nurkic returns come spring to take the latter’s place. Pau Gasol, health provided, is a perfect fit for the Blazers’ drop pick-and-roll coverage. They were average defensively last season after finishing sixth in defensive rating one year prior, regression most easily explained by a drop from first in defensive field goal percentage at the rim to 16th, per NBA.com. An uptick in rim-protection numbers is very possible and would do a lot toward stemming the negative influence of Portland’s decrease in defensive versatility.

But that trade-off is hardly a formality, and maybe wouldn’t be enough to offset a potential loss of flexibility on the other end. Aminu made small strides with the ball last season, finishing more awkward, herky-jerky drives without turning it over, but has never been imposing offensively. Harkless is cut from a similar cloth, though he enjoyed more success as a cutter and post-up option on switches.

Collins, as well as he moves for a seven-footer, doesn’t address those longstanding deficiencies for Portland. He can put the ball down two or three times on a short roll and is comfortable in the dribble hand-off game, but certainly won’t be grabbing defensive rebounds and rushing up the floor to create a winning numbers game. He’s also limited in terms of attacking close-outs – should his shooting improve to the point defenders deem aggressive contests necessary, of course.

Collins’ shot 33.1 percent from deep last season, a respectable number for a big with nascent stretch to the arc. But he took just 1.6 three-pointers per game, fewer than his rookie year, and a whopping 96 of his 121 attempts came absent any defender within six feet of him, per NBA.com.

Collins will get a lot of looks like this in October and November, and it’s imperative he knocks them down at a respectable clip – as much for the points as the space created by defenses feeling like they need to guard him outside the paint.

There’s a case to be made that Collins isn’t ready to log a lion’s share of his minutes at center.

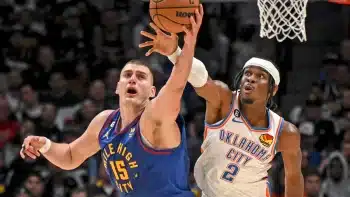

He’s still thin despite putting on noticeable muscle since he came into the league, a trait his unrelenting intensity and physicality hasn’t quite been able to overcome. Portland has long been one of the league’s best rebounding teams, but has struggled on both the offensive and defensive glass when Collins has played center over the past two seasons. Mason Plumlee, for instance, killed him on the offensive boards in the second round of the playoffs. Nikola Jokic, to no one’s surprise, bullied him one-on-one, mostly due to such a sizable discrepancy in strength and overall girth.

Maybe starting at power forward really is the next step toward Collins reaching his ultimate ceiling. It’s not like he’s going to be the Blazers’ best center soon anyway, not after Nurkic established himself as a consistent two-way force last season.

Still, asking so much of Collins with so little behind him seems like a mistake for a team looking to compete at the highest level right now. Lillard and McCollum, despite their tandem multi-year extensions this summer, aren’t getting any younger. The collapse of the Warriors’ juggernaut presents a golden opportunity for a long-shot team like Portland to win a title. Lillard probably won’t enter any remaining season of his career, at least in a Blazers uniform, with a better chance to hoist the Larry O’Brien Trophy in June than this one.

Collins alone won’t sink Portland’s championship hopes. Even in an expanded role, he won’t use enough possessions to loom quite so large. But the margins matter more than ever in a Western Conference where as many as six teams can talk themselves into title contention, and so much of the Blazers’ success on both ends hinges on a 21-year-old who seems stuck between positions and has only played more than 30 minutes once in his career to date.

Is Collins ready for so much additional responsibility? The answer could help inform the difference between extremes of Portland playing deep into spring and missing out on the playoffs altogether.